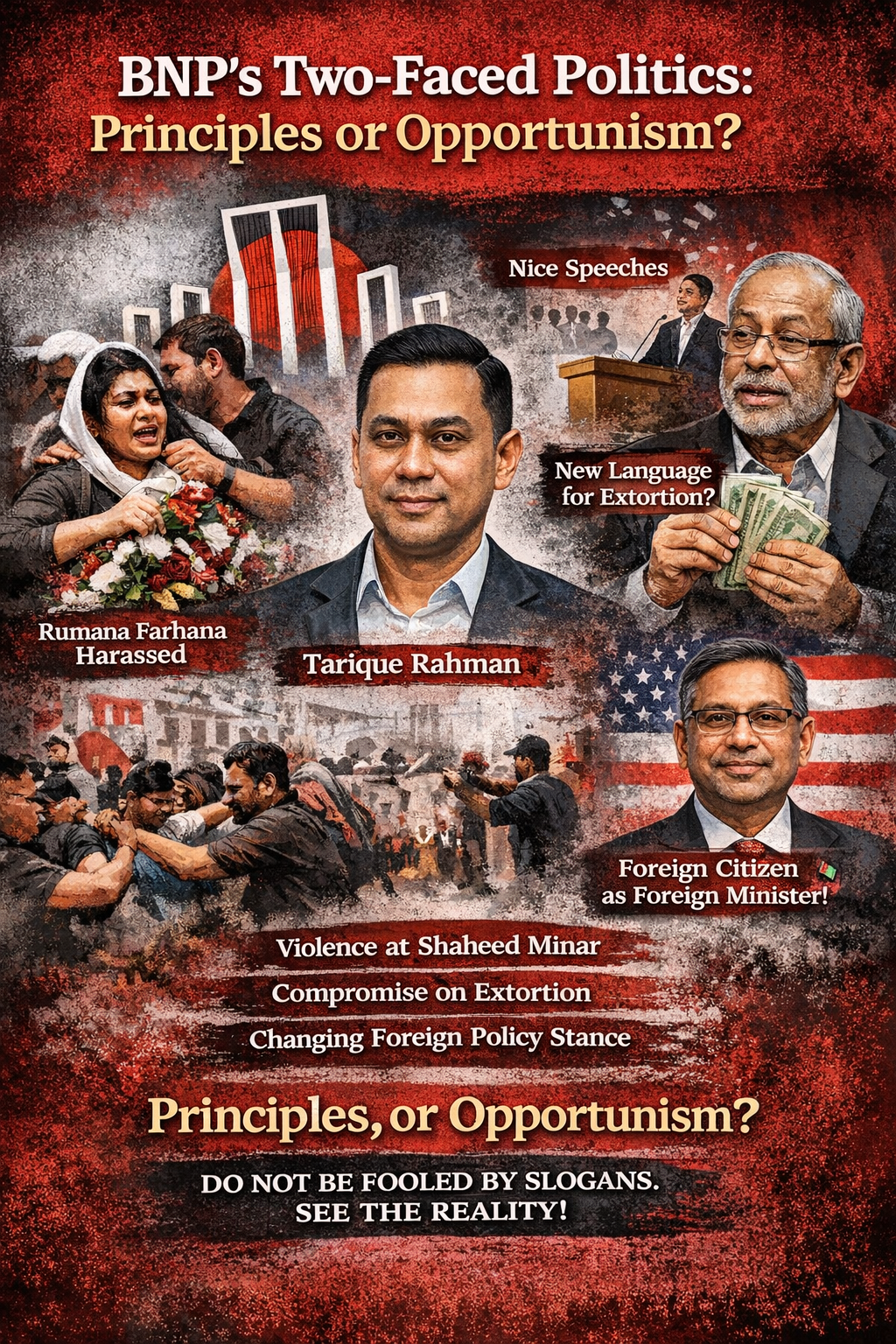

Apurbo Ahmed Jewel: When an elected representative—Rumina Farhana—is harassed and her wreath is torn apart, it cannot be dismissed as an isolated incident. It is a clear reflection of political culture. The question is: if a party that claims to uphold democracy cannot ensure tolerance even on the day of commemorating the language martyrs, what kind of politics is it truly practicing?

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) now appears to stand in a strange dual position. At the top, there are speeches about principles, reform, and civility. On the ground, there is aggression, disorder, and uncontrolled rhetoric. Does the top leadership genuinely not know what is happening, or do they know and choose silence? If such behavior can occur in front of cameras, what happens beyond them is difficult to imagine.

Acting Chairman Tarique Rahman often speaks of principles and a new style of politics. Yet the widening gap between words and actions has become the central crisis. Speeches about values cannot conceal chaos at the grassroots level. If discipline is not embedded in party culture, then it is nothing more than stage decoration.

Even more concerning is the manipulation of language around extortion. When a minister publicly claims that collecting money “by mutual understanding” is not extortion, it signals that the issue is not merely criminality, but mindset. When the law is clear, changing terminology to alter meaning becomes a strategy to normalize wrongdoing. Today it is called “compromise,” tomorrow perhaps a “cooperation fee.” Is the party attempting to rewrite the definition of extortion?

In the cultural sphere, there is also a visible identity crisis. Admiring foreign artists is not wrong, but sidelining one’s own legendary figures suggests a deeper insecurity. No nation strengthens itself by devaluing its own cultural heritage. Just as in politics, a lack of confidence in culture reflects weakness in leadership.

The most dramatic chapter lies in foreign policy. Individuals once accused of serious wrongdoing are now entrusted with high office. Were those past allegations merely political weapons? If they were false, the public was misled. If they were true, what does their present position say about consistency? In politics, selective memory can be convenient—but public memory is not so easily erased.

Taken together, these are not isolated incidents but a pattern: intolerance on Language Day, semantic maneuvers over extortion, cultural self-doubt, and shifting positions in foreign policy. The central question remains: is this politics driven by principle or by convenience? If principles are truly the foundation, they must be visible in conduct. If language changes daily to suit advantage, then it is not principle—it is strategy.

Democracy does not survive on slogans alone. It survives through behavior, self-criticism, and the courage to admit mistakes. Does that courage truly exist? Or is old politics simply returning under the banner of a “new” Bangladesh?